03

UNDERSTANDING HERITAGE OF RACISM IN THE U.S.

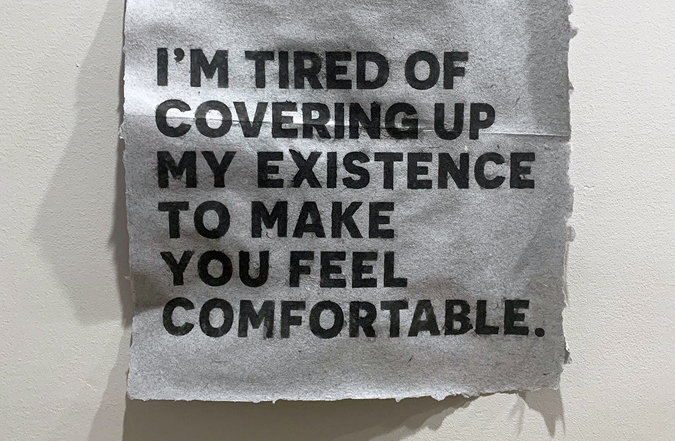

“I respond to it by challenging this idea that “different” is wrong or “bad,”

by attempting to set a new precedent in design and in the arts as a whole.

These industries have been forever dominated by white male minds,

we are attempting to flip that narrative and dismantle

what we were taught in order to build something new from the ground up.”

“I respond to it by challenging this idea that “different” is wrong or “bad,”

by attempting to set a new precedent in design and in the arts as a whole.

These industries have been forever dominated by white male minds,

we are attempting to flip that narrative and dismantle

what we were taught in order to build something new from the ground up.”

— Xena Brar, Graphic Design ’20

People are a product of culture. Different cultures convey different racial messages, and it is easy to see that these messages and perspectives are usually dictated by those in political power, the press, educational and religious institutions, and our family, friends, and neighbors.

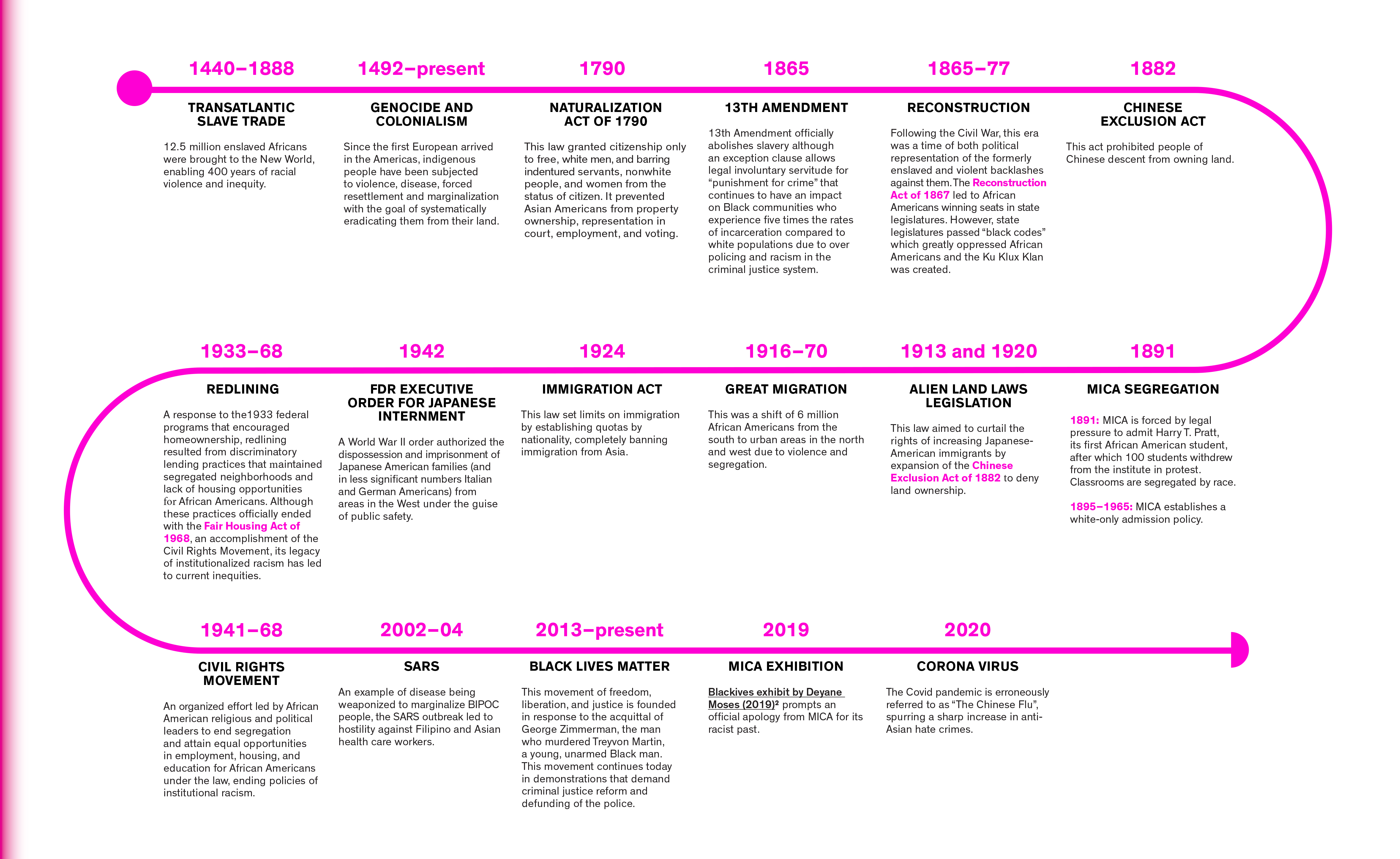

Since its beginning, the racialization (processes by which a group of people is defined by their “race”) of people has been used as justification for domination, exploitation, and violence. It persists today with the erasure of the indigenous peoples from our teaching of history and the continuation of unequal opportunities for Black, Indigeous, and People of Color (BIPOC.) Despite the differences in our experiences of race, there are deep commonalities if you look for them, especially between countries with a history of colonialism.

Since its beginning, the racialization (processes by which a group of people is defined by their “race”) of people has been used as justification for domination, exploitation, and violence. It persists today with the erasure of the indigenous peoples from our teaching of history and the continuation of unequal opportunities for Black, Indigeous, and People of Color (BIPOC.) Despite the differences in our experiences of race, there are deep commonalities if you look for them, especially between countries with a history of colonialism.

This section provides an overview of the racial history in the U.S and at MICA with emphasis on the experiences of African and Asian Americans.

The history of resistance

and resilience

Looking to historical events and U.S. racial policies to understand race only gives us a starting place. There is also the lived history of resistance−from the Underground Railroad to the present day Black Lives Matter activism, as well as families, faith communities, and nonprofit organizations who provide mutual support. A recognition of racial injustice should not overshadow an appreciation of the resilience of African Americans. From the first enslaved Blacks to today’s communities, African American culture is strengthened by extended family networks, grassroot organizations, community self-reliance, and places of worship.

Similarly, Asian Americans have also stood up to assure their rights through grassroots community organizing. For example, the Health Fair of 1971 in New York’s Chinatown addressed a lack of access to health care. Led by Asian American activists, many of whom were influenced by Civil Rights leaders, the ten day event resulted in the founding of a clinic which now serves 60,000 residents annually. A group of Chinese families in San Francisco filed a lawsuit that they took to the U.S. Supreme Court, ultimately assuring that schools must provide language support for non-native English speaking children (Lau v Nichols, 1974). And founded as a counter protest in 2018 in Los Angeles, the volunteer-run grassroots organization Ktown for All, provides direct aid and political advocacy to unhoused individuals in Koreatown regardless of their ethnic backgrounds.

The history of resistance

and resilience

and resilience

Looking to historical events and U.S. racial policies to understand race only gives us a starting place. There is also the lived history of resistance−from the Underground Railroad to the present day Black Lives Matter activism, as well as families, faith communities, and nonprofit organizations who provide mutual support. A recognition of racial injustice should not overshadow an appreciation of the resilience of African Americans. From the first enslaved Blacks to today’s communities, African American culture is strengthened by extended family networks, grassroot organizations, community self-reliance, and places of worship.

Similarly, Asian Americans have also stood up to assure their rights through grassroots community organizing. For example, the Health Fair of 1971 in New York’s Chinatown addressed a lack of access to health care. Led by Asian American activists, many of whom were influenced by Civil Rights leaders, the ten day event resulted in the founding of a clinic which now serves 60,000 residents annually. A group of Chinese families in San Francisco filed a lawsuit that they took to the U.S. Supreme Court, ultimately assuring that schools must provide language support for non-native English speaking children (Lau v Nichols, 1974). And founded as a counter protest in 2018 in Los Angeles, the volunteer-run grassroots organization Ktown for All, provides direct aid and political advocacy to unhoused individuals in Koreatown regardless of their ethnic backgrounds.

Similarly, Asian Americans have also stood up to assure their rights through grassroots community organizing. For example, the Health Fair of 1971 in New York’s Chinatown addressed a lack of access to health care. Led by Asian American activists, many of whom were influenced by Civil Rights leaders, the ten day event resulted in the founding of a clinic which now serves 60,000 residents annually. A group of Chinese families in San Francisco filed a lawsuit that they took to the U.S. Supreme Court, ultimately assuring that schools must provide language support for non-native English speaking children (Lau v Nichols, 1974). And founded as a counter protest in 2018 in Los Angeles, the volunteer-run grassroots organization Ktown for All, provides direct aid and political advocacy to unhoused individuals in Koreatown regardless of their ethnic backgrounds.

“I define racism as a mental plague that breeds hate, negative bias and misjudgment towards people of color.”

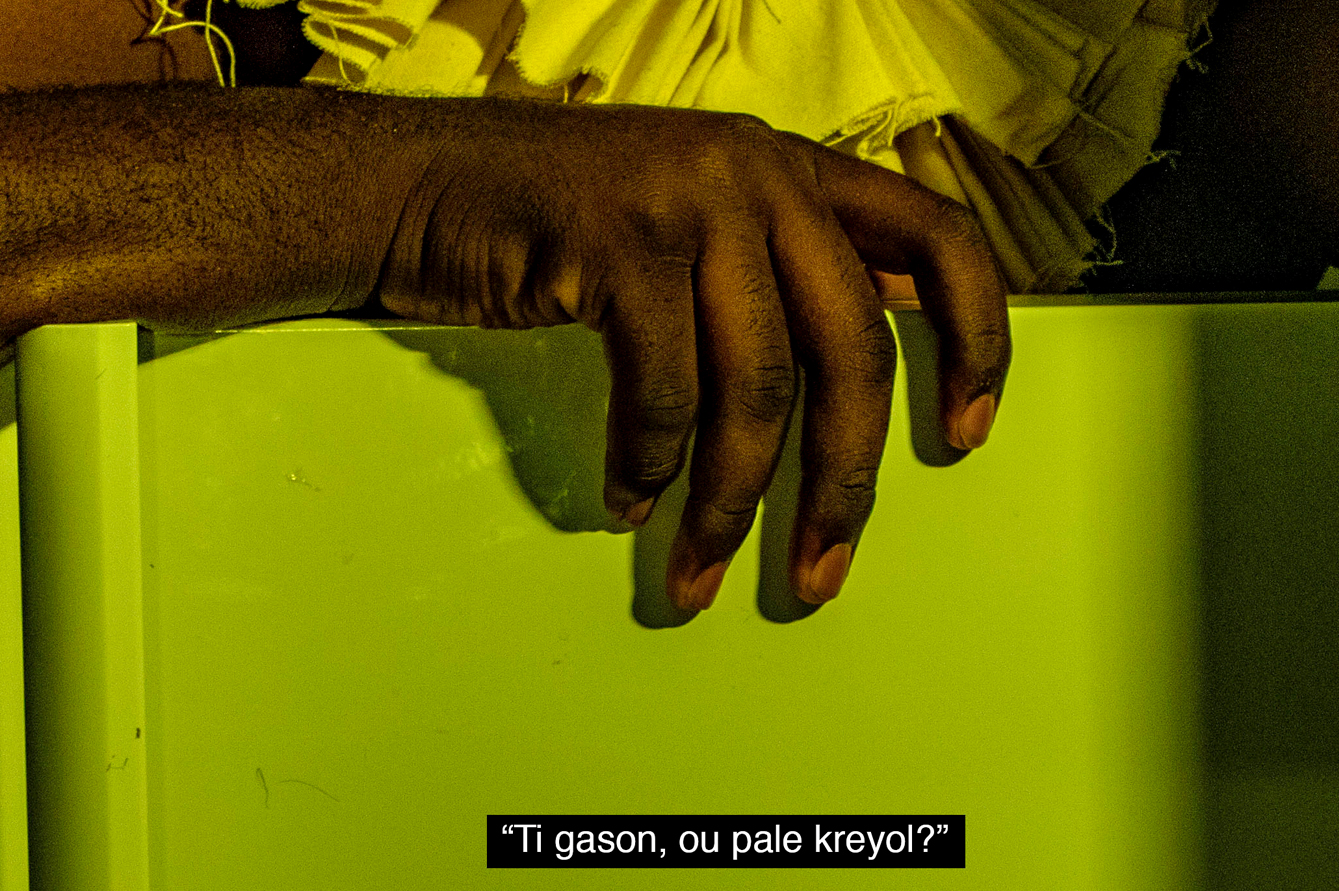

—Lia Latty, Photography ’22

Allyship

While the pandemic and social unrest have led to tension between different BIPOC groups, a study of racial history in the U.S. wouldn’t be complete without recognition of ways that Asian and Black communities have supported each other’s protests and social movements. For instance, Asian Americans Yuri Kochiyama and Grace Lee Boggs contributed to the Civil Rights movement. The longest student strike, the San Francisco State Student Strike of 1968−1969 was a collaboration between Black, Latinx, Asian, and Native American students in the Third World Liberation Front. The Fillipinno-American labor leader Philip Vera Cruz worked with Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers to improve the working conditions for migrant workers.

And today, groups like Asian American Advocacy Fund and the Asian American Pacific Islanders for Civic Empowerment have initiated projects such as the social media campaign Asians 4 Black Lives, Letters for Black Lives multi-lingual letters to discuss anti-Black racism with non-English speaking parents, and community resources such the Asian American Racial Justice Toolkit.

And today, groups like Asian American Advocacy Fund and the Asian American Pacific Islanders for Civic Empowerment have initiated projects such as the social media campaign Asians 4 Black Lives, Letters for Black Lives multi-lingual letters to discuss anti-Black racism with non-English speaking parents, and community resources such the Asian American Racial Justice Toolkit.

“Every time I create, every time I make, that is a direct response, a rebel, a politic.”

— James Balo, General Fine Art ’22 and MAT ’23